Goal:

Team:

2 UX Designers

3 UX Researchers

1 Project Lead

Design a digital mental health intervention tailored for individuals experiencing mental health issues as a result of long COVID.

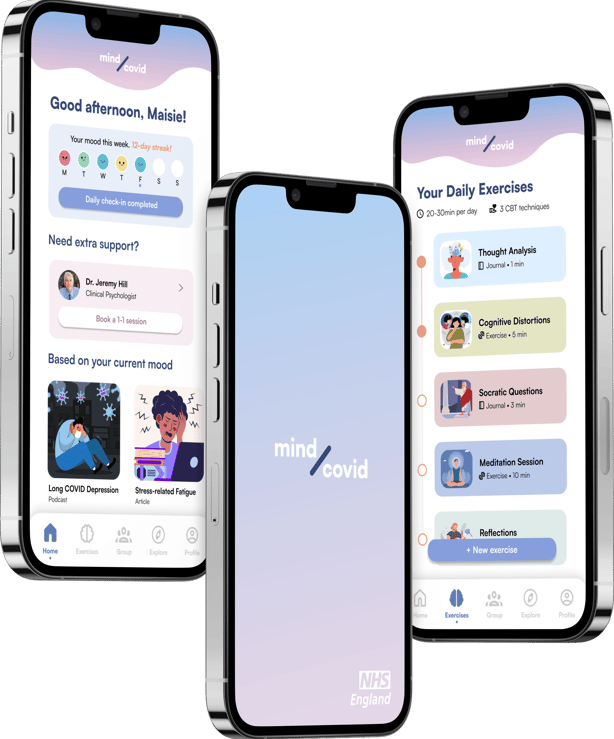

Mind/Covid: A CBT App for Long COVID Mental Health

Solution:

A CBT-based app that offers self-help tools and peer support to address depression, anxiety, and trauma from long COVID.

My role:

Lead UX Designer

Tools:

Figma, Miro, Excel, Canva

Timeline:

6 weeks

Understanding the problem

Recent research showed that 1 in 4 long COVID sufferers develop a mental health issue within 6 months - not solely due to physical illness but from psychological factors like isolation, trauma, and medical dismissal.

We aimed to fill this support gap with an accessible, therapeutic app grounded in user needs and behavioural science.

User research

We reviewed secondary data from:

14 long COVID forums and patient blogs

Academic literature on long COVID and mental health

Existing apps addressing chronic illness

Using affinity mapping and thematic analysis, we identified:

High prevalence of depression, anxiety, and PTSD

Users feel neglected by both peers and healthcare professionals

Physical and mental symptoms exacerbate one another

Existing apps lack social support options

Current mental health apps aren't personalised to long COVID

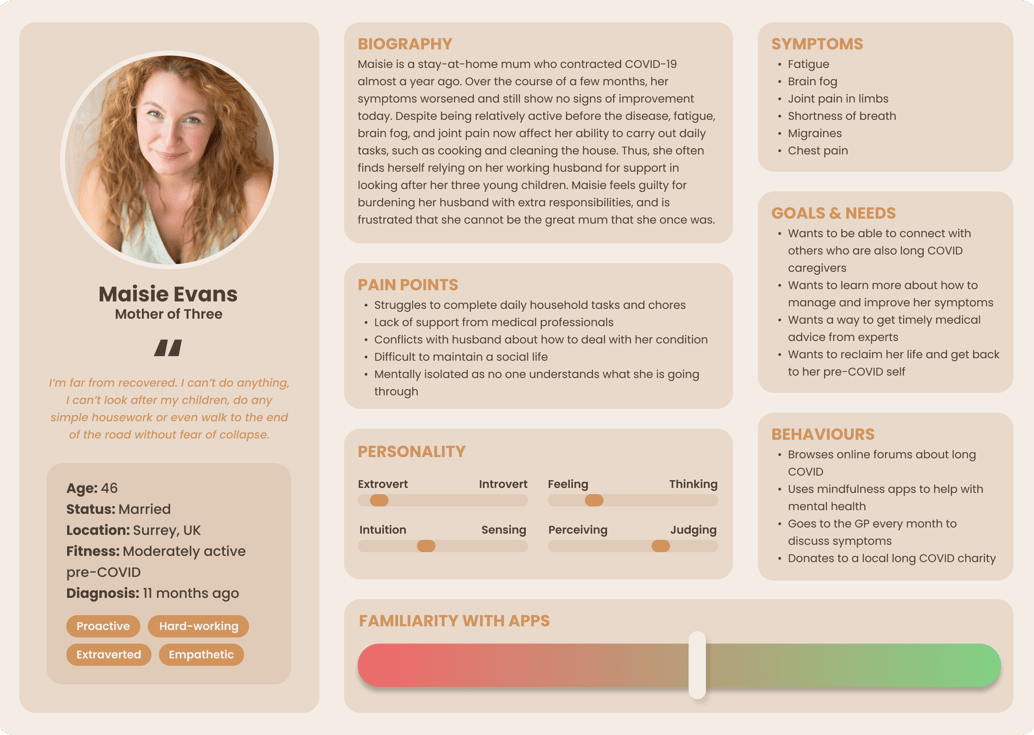

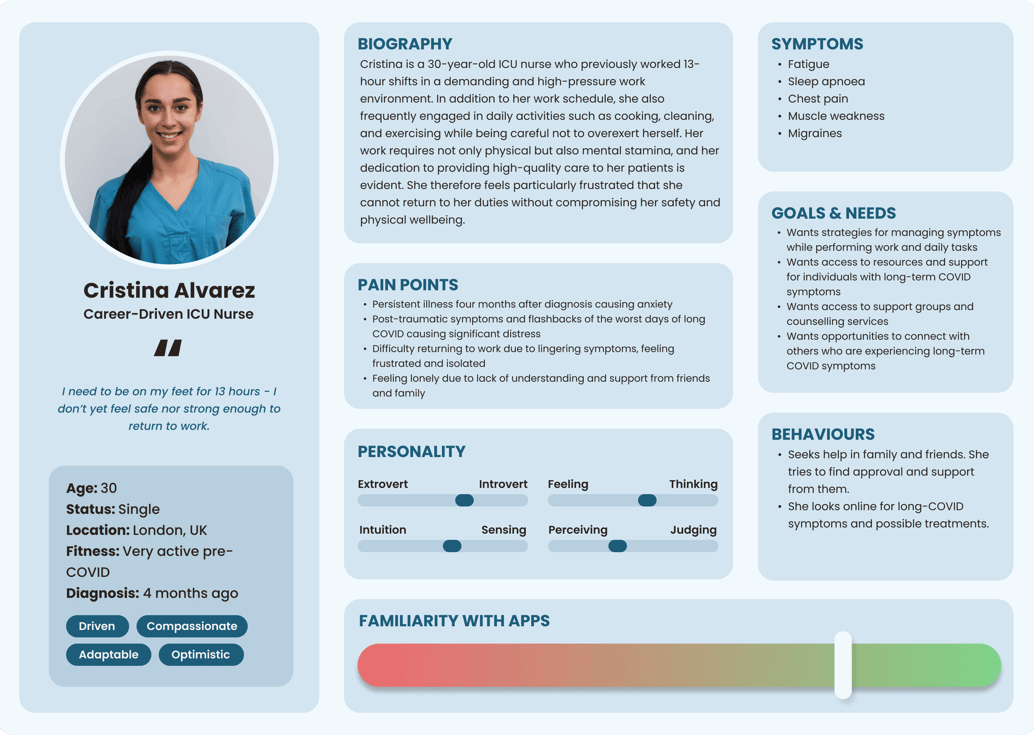

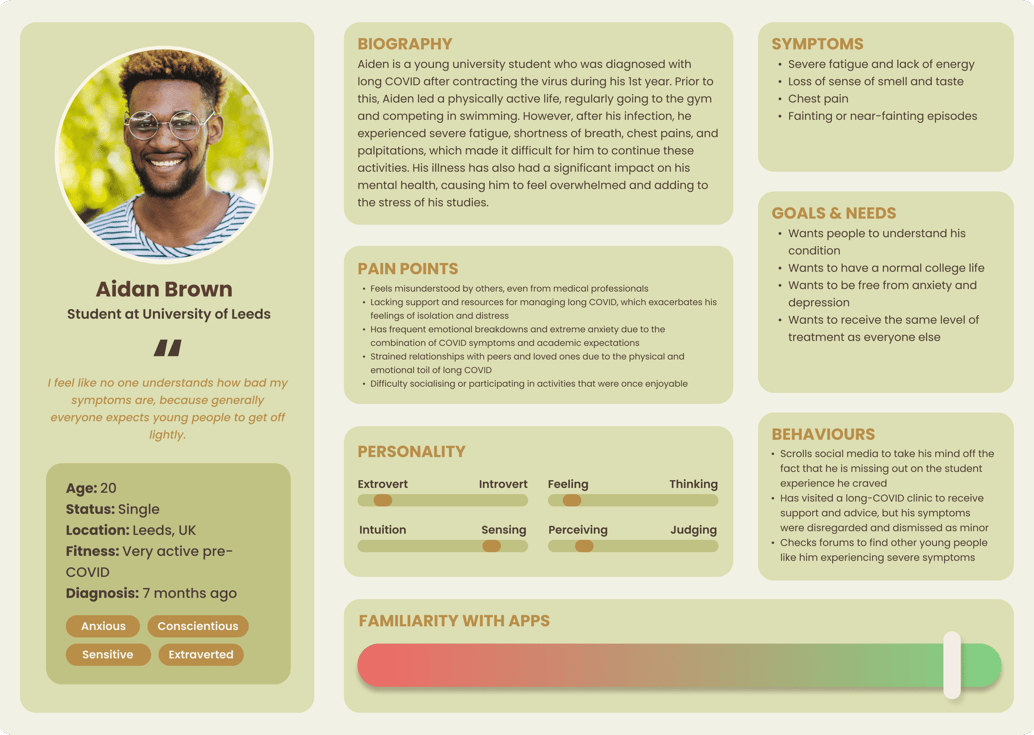

Creating personas

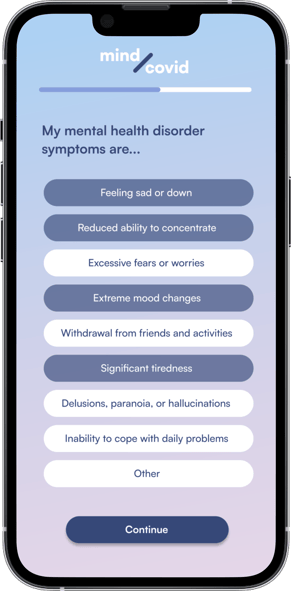

We created 3 user personas, each representing a common mental health condition tied to long COVID:

User requirements

To move from broad user insights to actionable design requirements, we applied the 5W1H (Who, What, When, Where, Why, How) framework to translate key themes from our user research into 4 core user needs:

✅ Must connect long COVID sufferers

✅ Should provide up-to-date information for better understanding

✅ Should help with managing and reducing mental health symptoms

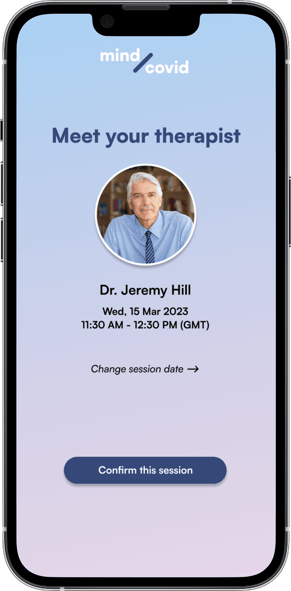

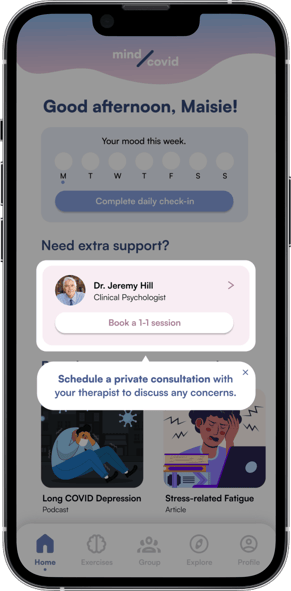

✅ Could provide timely access to medical professionals

Prototyping

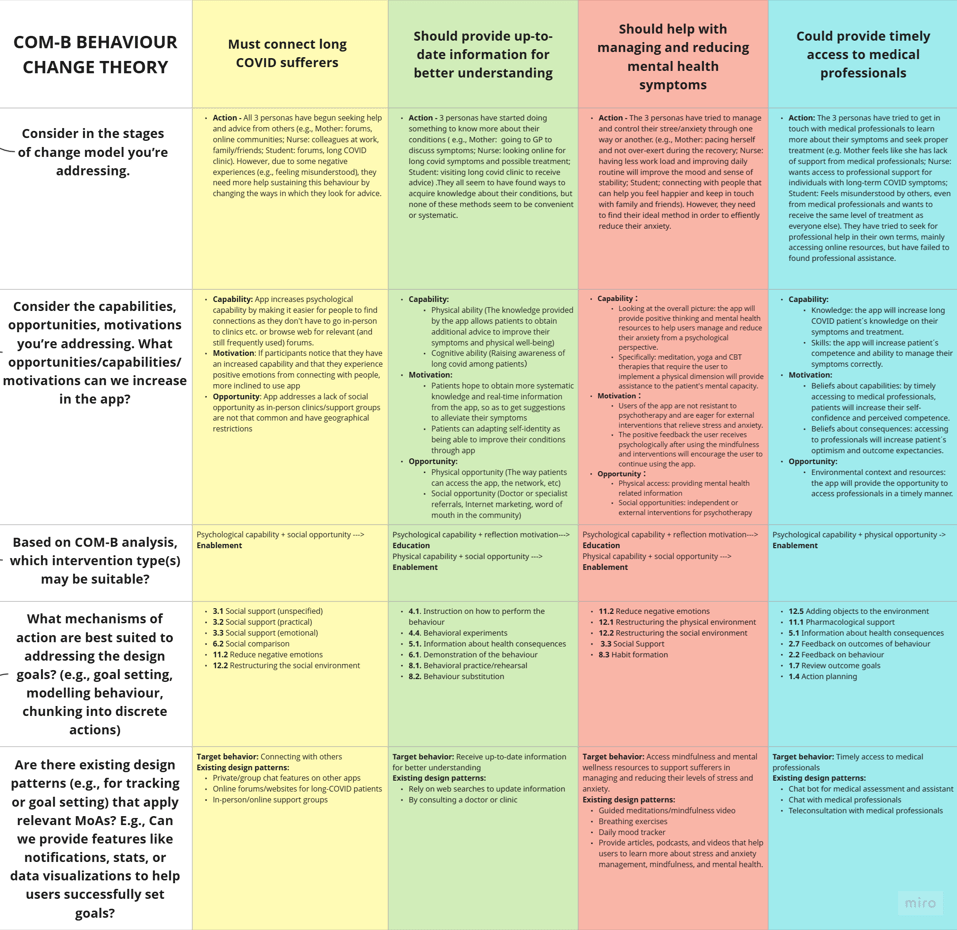

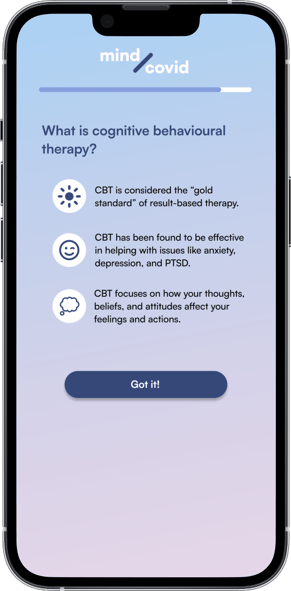

COM-B theory

To ensure that our design would facilitate our desired outcomes, we applied the COM-B model of behaviour change to brainstorm app features:

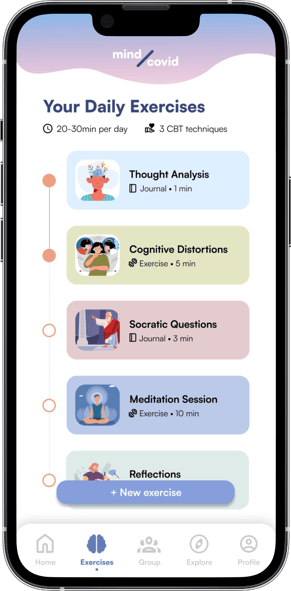

Capability: Psychological understanding of CBT tools

Opportunity: Low-effort peer connection

Motivation: Ongoing encouragement and emotional safety

We mapped these to appropriate mechanisms of action (MoAs) using behavioural science frameworks.

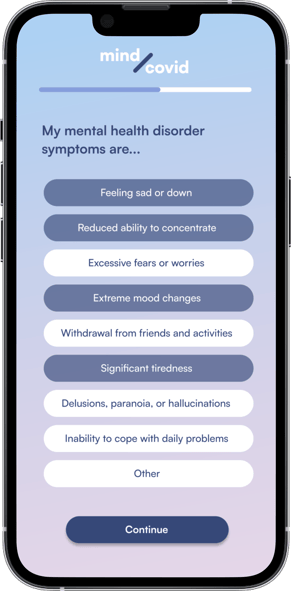

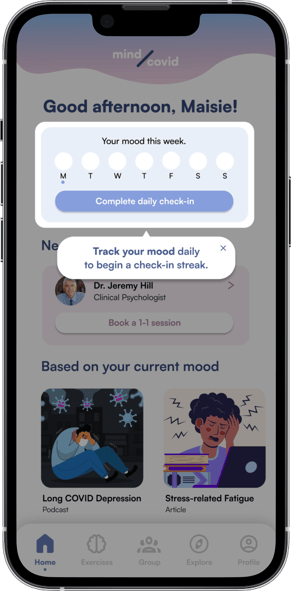

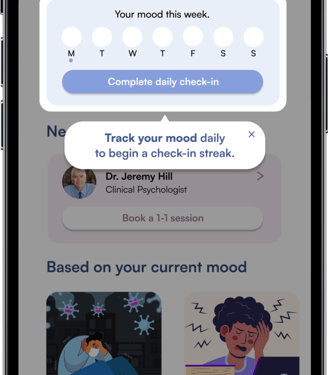

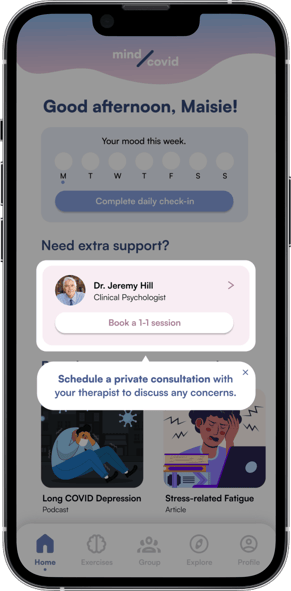

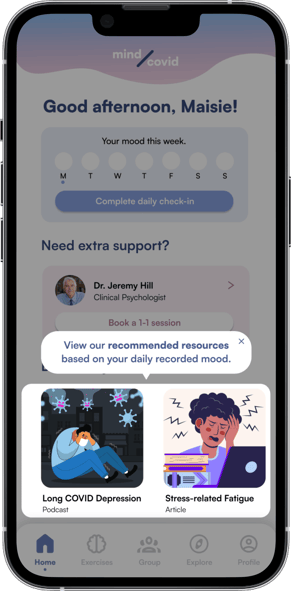

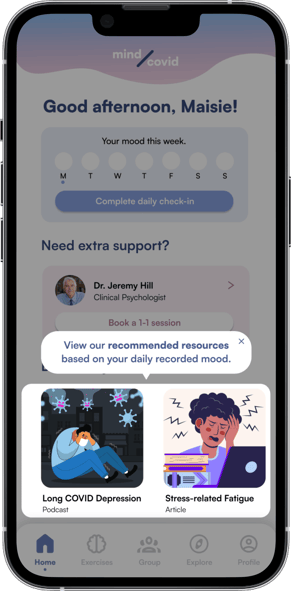

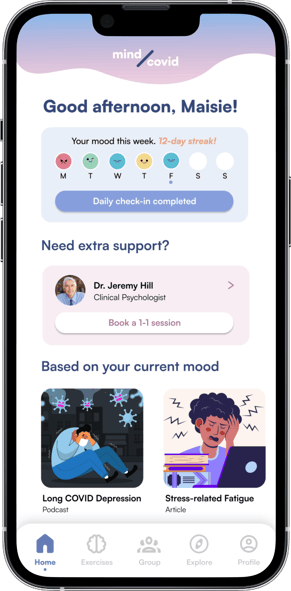

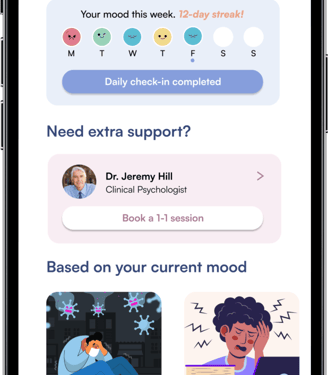

Key app features

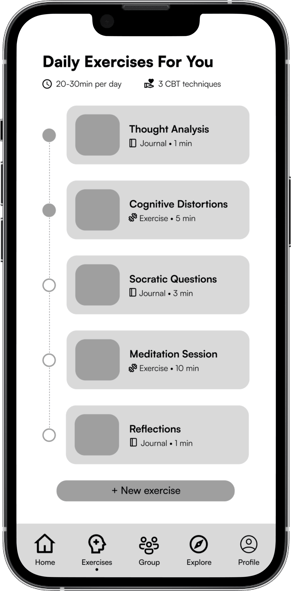

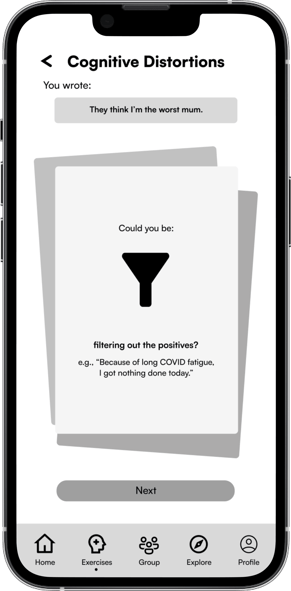

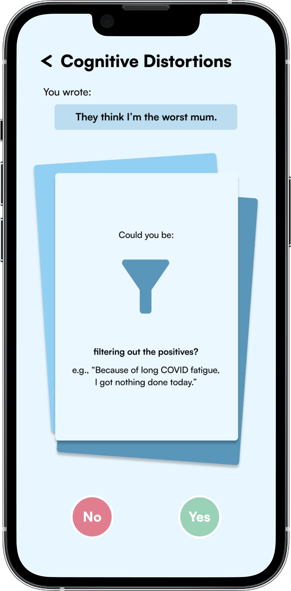

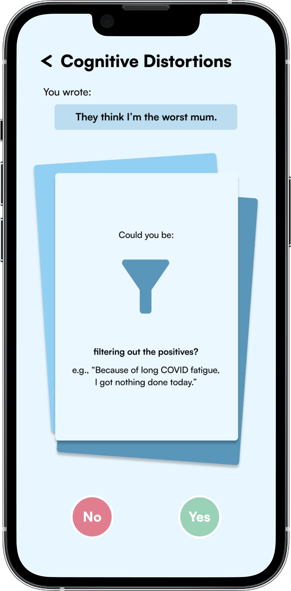

Self-Guided CBT Exercises

Tailored to user’s specific mental health condition

Long COVID examples used to increase relevance

Daily push notifications support habit formation

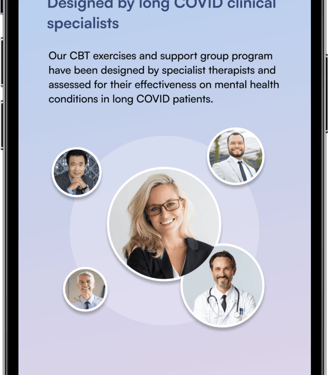

Based on evidence from Nakao et al. (2021) and Adamson et al. (2020)

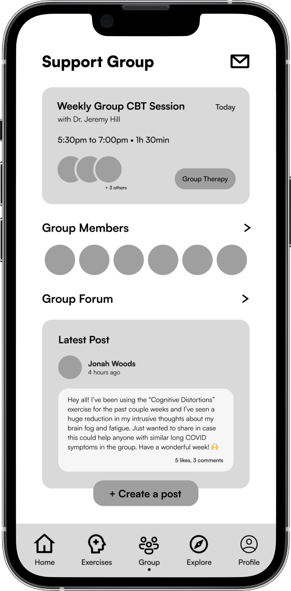

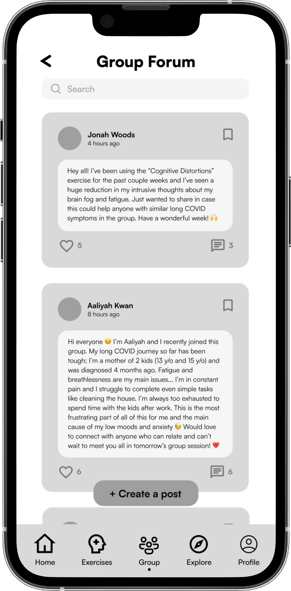

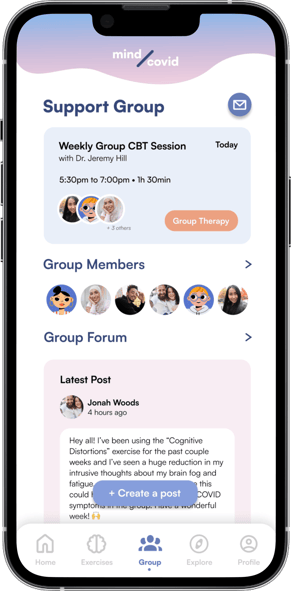

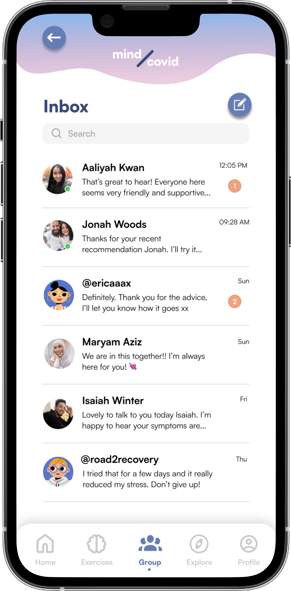

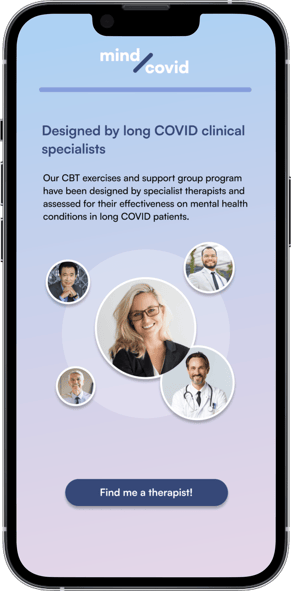

Therapist-Led CBT Support Groups

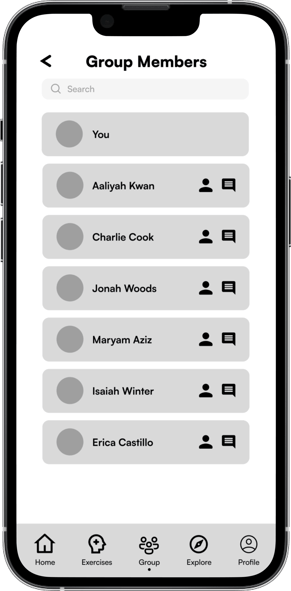

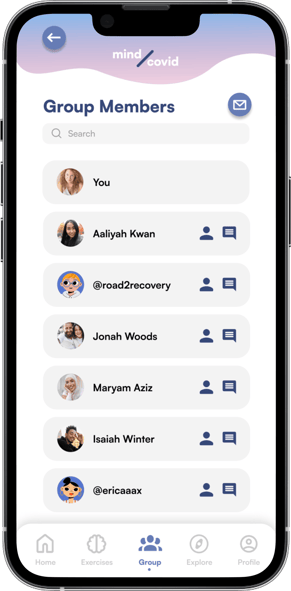

Algorithmically matched based on symptoms

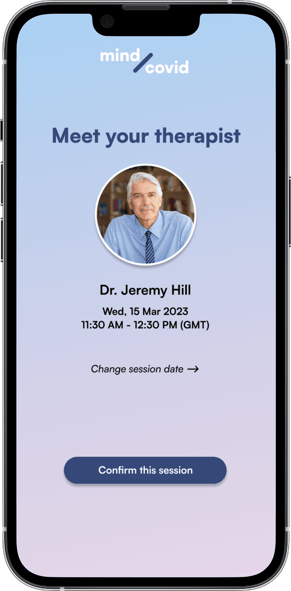

Weekly online sessions with licensed therapists

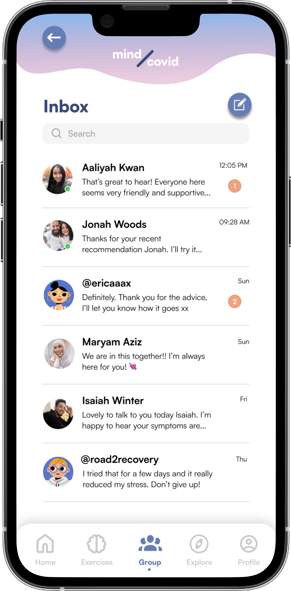

Optional forum for sharing stories and progress

Combines self-guided + peer-supported therapy

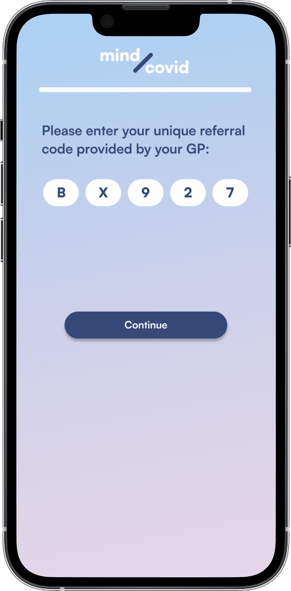

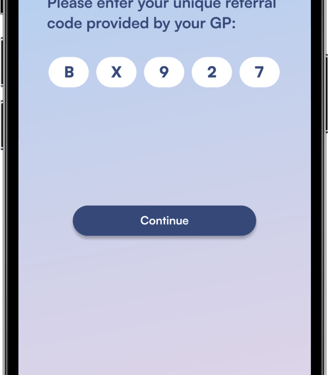

NHS-integrated support

Mind/Covid would be referral-based via the NHS

Ensures therapist availability and peer group consistency

Offers specialised mental health care for long COVID patients, unlike general wellness apps

User testing

Method

6 participants, each embodying a persona

Think-aloud usability test with scenario tasks

Follow-up interviews + Likert-scale feedback

Key findings

Privacy concerns

Users unsure if their data would be safe

✅ Fixes:Added GDPR/privacy onboarding screen

NHS branding for medical trust

Option to use pseudonyms and avatars

Feature confusion

Some unclear how users get assigned to groups

App onboarding felt lacking for new users

✅ Fixes:Added onboarding sequence explaining matching process

Introduced in-app tutorials via Settings

Key takeaways

1. Designing for mental health means leading with empathy, not just usability.

Working on Mind/Covid taught me that when users are already vulnerable, small design decisions can have big emotional weight. Every word, colour, and feature needed to feel safe and respectful. We weren’t just designing an app, we were designing a space that users could trust with their wellbeing.

2. Good research means meeting users where they are.

Because long COVID sufferers are often isolated and fatigued, traditional research methods weren’t always accessible. Turning to forums and personal narratives gave us unexpected depth and nuance. It reminded me that listening well sometimes means being creative with where and how you listen.

3. Behaviour change needs structure, not just motivation.

Using the COM-B model helped shift our thinking: it’s not enough to tell people what’s good for them, you have to remove friction, offer support, and make the healthy action feel achievable. It was a powerful reminder that thoughtful UX is often invisible, but deeply impactful.